How can we implement a polymorphic enum to mimic the Java ones ?

In a previous post, as an answer to @cyriux’s one, I showed how we could try to use a polymorphic enum in C# in order to mimic the Java ones. I have ported to C# the Java samples, using a base class called PolymorphicEnum. In this post, I’m going to give details about the implementation of this class.

The very first objectives are :

- To create an enum that derives from a base PolymorphicEnum.

- This derived enum must be able to define a set of values.

Getting started

What I want to be able to write is something like :

public class SomeEnum : PolymorphicEnum

{

public static SomeEnum FirstValue;

public static SomeEnum SecondValue;

}

As I can’t change the compiler behaviour, the two values declared in the previous sample must be instantiated somehow. The declaration then becomes :

public class SomeEnum : PolymorphicEnum

{

public static SomeEnum FirstValue = Register();

public static SomeEnum SecondValue = Register();

}

In order to be able to write such code, here is what I can do :

- First, the class I want to define is only meant to be derived from, so it must be abstract. Therefore, it can only be a class, and not a struct. So I’ll have to override the Equals and GetHashCode methods in order to get a value comparison behaviour for two different instances of enums. But if the singleton-ness is implemented properly… I should never have two instances !

- The class will have a generic Ordinal read-only property, where T is a value type. If not provided, this type will be an int by default.

- In order to instantiate enum values, the base class will have to expose a static protected method “Register”.

This leads us to this basic definition :

public abstract class PolymorphicEnum<T>

where T : struct, IComparable<T>, IConvertible

{

public T Ordinal { get; private set; }

public string Name { get; private set; }

protected PolymorphicEnum()

{

}

public override string ToString()

{

return this.Name;

}

}

And in order to get an int as the default underlying type, we define a derived class :

public abstract class PolymorphicEnum : PolymorphicEnum<int>

{

}

Adding registration

Ok, this has been quite simple. Now, we want the base class to allow its children to register instances. This means the base class will be responsible for instantiating, registering and tracking these instances. In order for the base class to instantiate the derived classes, we need to know their type in the method. To to this, we introduce a generic type parameter. We also want this method to accept an optional “ordinal” parameter, to handle the case where the ordinal values are defined by user-code. What we need is a method of the form :

protected static TEnumInstance Register<TEnumInstance>(

Nullable<T> ordinal = null)

where TEnumInstance : new()

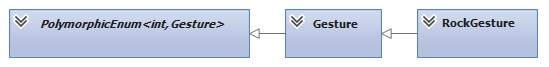

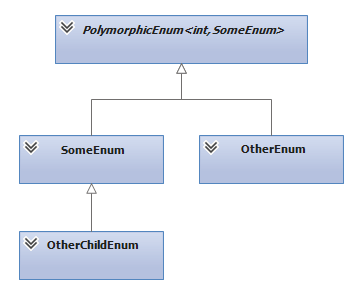

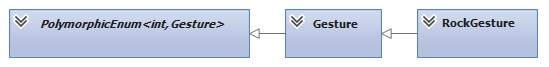

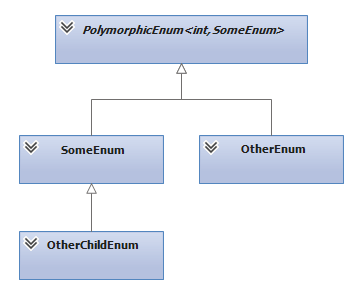

Notice the “new()” generic constraint on the type parameter : the given type has to have a parameter-less constructor, which we’ll use to instantiate it. But as we go towards the polymorphic behaviour, the enum class that we’ll have to instantiate can be a sub-class from the actual enum type ! For instance, if we take the first sample from the previous post, we have the following inheritance :

Because we do not want to give both of these type arguments on each Register call, the TEnum type argument moves up to the class level, and the class definition and Register method signature shift the following way:

public abstract class PolymorphicEnum<T>

where T : struct, IComparable<T>, IConvertible

|

=> |

public abstract class PolymorphicEnum<T, TEnum>

where T : struct, IComparable<T>, IConvertible

where TEnum : PolymorphicEnum<T, TEnum>, new()

|

protected static TEnumInstance Register<TEnumInstance>(

Nullable<T> ordinal = null)

where TEnumInstance : new()

|

=> |

protected static TEnum Register<TEnumInstance>(

Nullable<T> ordinal = null)

where TEnumInstance : TEnum, new()

|

The registration of the enum values is performed in a static dictionary, so here is at last the register method :

protected static TEnum Register<TEnumInstance>(

Nullable<T> ordinal = null)

where TEnumInstance : TEnum, new()

{

if (!ordinal.HasValue)

{

ordinal = registeredInstances.Any()

? registeredInstances.Keys.Max().PlusOne()

: default(T);

}

TEnum instance = new TEnumInstance();

instance.Ordinal = ordinal.Value;

registeredInstances.Add(ordinal.Value, instance);

return instance;

}

Comment : how to implement a “PlusOne” extension method, that could increment any of the underlying types supported by an enum, has been a puzzle of its own… See this post for my solution !

Simplifying registration

From now on we can register enum value the following way :

public class SomeEnum : PolymorphicEnum<SomeEnum>

{

public static SomeEnum FirstValue = Register<SomeEnum>();

public static SomeEnum SecondValue = Register<SomeEnum>();

}

Wait !? Why must we provide the type to the Register method, if that is the same as the generic argument of the class ? Let’s move forward and define an additional Register method :

protected static TEnum Register(Nullable<T> ordinal = null)

{

return Register<TEnum>(ordinal);

}

And the registration gets simpler again :

public class SomeEnum : PolymorphicEnum<SomeEnum>

{

public static SomeEnum FirstValue = Register();

public static SomeEnum SecondValue = Register();

}

Finding the names

So now we can register enum values, optionally specifying the ordinal value… but we’re not done yet ! I mean, aren’t we supposed to be able to convert enums from and to strings ? From the previous steps, we have a Name property with a private setter, and an overridden ToString() method. But the Name property is never set ! In my first implementations, providing the Register method with the string to associate with the value was mandatory. I was not satisfied with this solution, and I came up with the following replacement solution :

- I added a static field to the class :

private static bool namesInitialized = false;

- I replaced the Name property implementation with this new one :

private string name = null;

private string Name

{

get

{

EnsureNamesInitialized();

return this.name;

}

set

{

this.name = value;

}

}

- I implemented the EnsureNamesInitialized method :

protected void EnsureNamesInitialized()

{

if (!namesInitialized)

{

MemberInfo[] enumMembers = typeof(TEnum).GetMembers(

BindingFlags.Public

| BindingFlags.Static

| BindingFlags.GetField);

foreach (FieldInfo enumMember in enumMembers)

{

TEnum enumValue =

enumMember.GetValue(null) as TEnum;

if (enumValue != null)

enumValue.Name = enumMember.Name;

}

namesInitialized = true;

}

}

- And finally I added this line at the end or the register method, just before the “return instance” statement :

namesInitialized = false;

This mechanism ensures that the enum names are all computed using reflection. It assigns each enum value the name of the public static member to which it has been assigned (given the member has already been assigned and is of the correct type).

Serializing and deserializing

Nice ! We’ve made progress, really. Now we want to be able to serialize and deserialize the values from and to strings, as well as from the underlying primitive type.

Serializing to a string has been implemented from the start by the ToString() method. Deserializing will imply 4 methods signatures :

- bool TryParse(string value, out TEnum result)

- bool TryParse(string value, bool ignoreCase, out TEnum result)

- TEnum Parse(string value)

- TEnum Parse(string value, bool ignoreCase)

In the end the implementation is the following :

public static bool TryParse(string value,

bool ignoreCase,

out TEnum result)

{

TEnum[] instances = registeredInstances

.Values

.Where(

e => e.Name.Equals(

value,

ignoreCase

? StringComparison.InvariantCultureIgnoreCase

: StringComparison.InvariantCulture))

.ToArray();

if (instances.Length == 1)

{

result = instances[0];

return true;

}

else

{

result = default(TEnum);

return false;

}

}

The 3 other signatures simply rely on the previous method.

Concerning the other type of conversion (i.e. from and to the underlying primitive type), to stay as close as possible as how classical enums work, I have defined the following operator :

public static implicit operator T(PolymorphicEnum<T, TEnum> x)

{

return x.Ordinal;

}

And the second one :

public static explicit operator PolymorphicEnum<T, TEnum>(T x)

{

TEnum enumInstance;

if (!registeredInstances.TryGetValue(x, out enumInstance))

throw new ArgumentException(

string.Format("Enum value {0} not found", x, "x"));

return enumInstance;

}

Embedding data

Now we’re going to add an extra requirement : we want to embed data in the enum values. In order to store this values, I’ll be as open as I can and add an extra property typed as “object” :

protected object Data { get; private set; }

I’ll also add an extra optional parameter in the two Register methods, that become :

protected static TEnum Register(

Nullable<T> ordinal = null,

object data = null)

{

return Register<TEnum>(ordinal, data);

}

and :

protected static TEnum Register<TEnumInstance>(

Nullable<T> ordinal = null,

object data = null)

where TEnumInstance : TEnum, new()

{

if (!ordinal.HasValue)

{

ordinal = registeredInstances.Any()

? registeredInstances.Keys.Max().PlusOne()

: default(T);

}

TEnum instance = new TEnumInstance();

instance.Ordinal = ordinal.Value;

instance.Data = data;

registeredInstances.Add(ordinal.Value, instance);

namesInitialized = false;

return instance;

}

As you can see, not much as changed, but that is all there is to do ! A single point to mention is that nothing prevents the derived classes to change the state of the objects stored in the “Data” property. So when writing these derived classes, the developer has to be careful to enforce immutability.

Enforcing consistency

OK, I’ll soon stop this never-ending post, but there is a last detail that I wanted to explain, that is how I take care that once the set of values of an enum has been defined, it cannot be extended from any other class.

In order to register new values, you have to add new enum instances in the registeredInstances member. The way to do this is to call one of the two overloads or the Register method. If you wanted to bypass these methods, you would need to have access to the registeredInstances member, which is private in the base class, so that settles this point. But what prevents you from calling the Register methods in weird situations ? Let’s take a look at the following inheritance :

Put in code, it becomes :

public class SomeEnum : PolymorphicEnum<SomeEnum>

{

public static SomeEnum FirstValue = Register();

public static SomeEnum SecondValue = Register();

}

public class OtherEnum : PolymorphicEnum<SomeEnum>

{

public static SomeEnum ThirdValueAttempt = Register();

}

public class OtherChildEnum : SomeEnum

{

public static SomeEnum FourthValueAttempt = Register();

}

The above code is valid, and compiles without any warning. The register method is a protected method, so it can be called :

- from any class deriving from the same base classe PolymorphicEnum<T> (with the same T type), for instance here the OtherEnum class,

- from any sub-class, for instance here the OtherChildEnum class.

To prevent the registration of invalid values, we check at the very beginning of the Register method that the type which called the method is the same as the type being registered. To do so, we take a look at the call stack, either at the first or the second stack frame, depending on the overload of Register that was called :

StackFrame frame = new StackFrame(1);

if (frame.GetMethod().Name == "Register")

frame = new StackFrame(2);

MethodBase enumConstructor = frame.GetMethod();

if (enumConstructor.DeclaringType != typeof(TEnum))

throw new EnumInitializationException(

"Enum members cannot be registered from other enums.");

This prevents the user code from registering undesired values. But there is still an edge case to be handled, pointed to me be @cyriux…

Let me show you what’s wrong… Remember the very first sample about the gestures ? Don’t look back ! Here is the code again :

/** PolymorphicEnum have behavior! **/

public class Gesture : PolymorphicEnum<Gesture>

{

public static Gesture ROCK = Register<RockGesture>();

public static Gesture PAPER = Register();

public static Gesture SCISSORS = Register();

// we can implement with the integer representation

public virtual bool Beats(Gesture other)

{

return this.Ordinal - other.Ordinal == 1;

}

private class RockGesture : Gesture

{

public override bool Beats(Gesture other)

{

return other == SCISSORS;

}

}

}

The problem with this implementation is maybe not that obvious, but what if I write the following code ?

public class Godzilla : Gesture

{

public static Godzilla Instance = new Godzilla();

public override bool Beats(Gesture other)

{

return true;

}

}

Yes, this is valid code. And the following test is green !

[TestMethod]

public void godzilla_beats_all()

{

Assert.IsTrue(Godzilla.Instance.Beats(Gesture.ROCK));

Assert.IsTrue(Godzilla.Instance.Beats(Gesture.PAPER));

Assert.IsTrue(Godzilla.Instance.Beats(Gesture.SCISSORS));

}

Now imagine if the Gesture enum was part of a library… Nothing would prevent user code from providing a Godzilla instance wherever a Gesture is asked…

There are several ways to secure this implementation :

- The logic could be provided as embedded data in the registration or the enum (using a lambda expression). Although this is the solution I would prefer (“composition over inheritance”, see the Manifesto for Not Only Object-Oriented Development), this would not be a real polymorphic behaviour anymore !

- If we want to solve this using polymorphism, this is what I came up with. I added the following two “Checked” methods and the IsRegistered property in the base class :

private bool IsRegistered

{

get { return registeredInstances.Values.Contains(this); }

}

protected TEnum Checked(TEnum value)

{

if (!value.IsRegistered)

throw new UnregisteredEnumException(

"This enum is not registered");

return value;

}

protected void Checked(Action a)

{

if (!IsRegistered)

throw new UnregisteredEnumException(

"This enum is not registered");

a.Invoke();

}

protected TReturn Checked<TReturn>(Func<TReturn> f)

{

if (!IsRegistered)

throw new UnregisteredEnumException(

"This enum is not registered");

return f.Invoke();

}

Using these new methods, here is how we could rewrite the previous “Godzilla” sample :

public class CheckedGesture : PolymorphicEnum<CheckedGesture>

{

public static CheckedGesture ROCK = Register<RockGesture>();

public static CheckedGesture PAPER = Register();

public static CheckedGesture SCISSORS = Register();

// we can implement with the integer representation

public bool Beats(CheckedGesture other)

{

return Checked(() => this.BeatsImpl(Checked(other)));

}

protected virtual bool BeatsImpl(CheckedGesture other)

{

return this.Ordinal - other.Ordinal == 1;

}

private class RockGesture : CheckedGesture

{

protected override bool BeatsImpl(CheckedGesture other)

{

return other == SCISSORS;

}

}

}

And the method that can be overridden in the new Godzilla class in now the BeatsImpl one :

public class CagedGodzilla : CheckedGesture

{

public static CagedGodzilla Instance = new CagedGodzilla();

protected override bool BeatsImpl(CheckedGesture other)

{

return true;

}

}

This now works correctly and the CagedGodzilla can’t be used in place of a CheckedGesture without throwing an UnregisteredEnumException. But this seems a little bit over-engineered, isn’t it ?

All of this horrible mess is available on my GitHub, along with the unit tests and the different steps of the implementation, which I’ve described in this post.

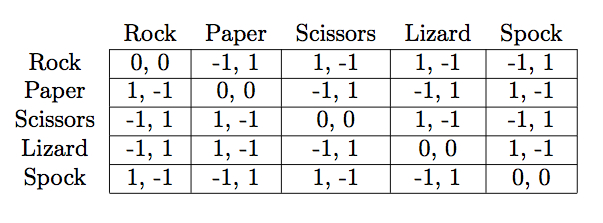

If you follow the link, you’ll get to a Google Play application that allows you to play the (in-)famous

If you follow the link, you’ll get to a Google Play application that allows you to play the (in-)famous