This post is part of the F# Advent Calendar in English 2016 project. Check out all the other great posts there! And special thanks to Sergey Tihon for organizing this.

I’m very happy that F# is getting used more and more in my work place. It has even got to a point where some code has been written a while ago and maintenance is done by someone who hasn’t been involved in the project at all in the beginning. This has been an chance to work on a somewhat “legacy” F# code, which was the first time for me. The code on which we’ve worked had been written by someone who was a well-grounded C# dev, but not fluent in F#. Let’s say that the produced F# code is not very idiomatic. After going through this code, here is some advice I’d like to give to beginners.

I’m very happy that F# is getting used more and more in my work place. It has even got to a point where some code has been written a while ago and maintenance is done by someone who hasn’t been involved in the project at all in the beginning. This has been an chance to work on a somewhat “legacy” F# code, which was the first time for me. The code on which we’ve worked had been written by someone who was a well-grounded C# dev, but not fluent in F#. Let’s say that the produced F# code is not very idiomatic. After going through this code, here is some advice I’d like to give to beginners.

Disclaimer: I’m talking about regular code here, there is no particular constraint on performance nor memory (this is not real-time nor high-frequency trading). We can afford to allocate memory and trigger GC collections. The advice given here may not be relevant to your specific use-case.

Type all the things

While gradually building something in F#, you’ll probably use tuples, because they’re so easy to use. And when writing a function, adding a new parameter is really easy, so of course you’ll do. However, if you keep doing that, you end up with code that’s difficult to maintain. The classical answer in a statically typed functional language for such a problem is “add more types”.

If you find yourself using:

- tuples with too many items in it: use a type to name your items (a record for instance)

- record types with too many properties: compose smaller types to group related properties

- higher-order functions: define a type for each non-trivial function signature you consume or return

- functions with too many arguments: group arguments with types (but still remember points 1 & 2)

Keep things simple

This applies to any language, and is not F# specific. However when some people start to “get” how F# works, they tend to over-complicate things, where they could have been kept simple. Don’t forget the common sense good practices that apply to other languages, just because you’re coding in F#. FSharpLint (available as part of F# Power Tools) is a tool that can help you with that. In particular, it enforces the use of:

- small functions

- even smaller lambdas

- small tuples only (4 items max, and I’d say 4 is already too much)

Piping

Piping is super cool. I acknowledge that. In my opinion, it allows you to easily express the “flow” of data through steps, and is very expressive. However that doesn’t mean you should go crazy with pipes.

Piping into 10 steps of complicated filters, grouping, and folds, is not as readable after 6 months as you thought it was when you were writing it. Comments could help, but defining steps in named variables, and composing them in the end, is very easy to do and will allow you to express the intent directly in the code.

Curried functions

Curried functions only make sense if you can do partial applications that also make sense. If your arguments don’t make any sense if they’re not provided together, they compose a single unit of meaningful data, and you should:

- either group those items in a tuple,

- or (most probably) define a type.

Higher-order functions

“Higher-order” means that at least one parameter of the function is going to be a function itself. Why not? Functions are first-class citizens. However, don’t try to be too smart. Remember, “Keep things simple”. Taking functions as parameter is one thing, but taking higher-order functions as parameters starts to become complicated. There can probably be cases where it makes sense, but don’t overuse it. And if you need to take functions as parameters, consider defining meaningful types for theses function signatures.

Explicit side-effects

F# is not a pure functional language, as it doesn’t prevent you from mutating state or having side-effects in your code. However, when you write a function that has side effects, make it as explicit as you can. Don’t hide a function that has side effects in the middle of a call chain, unless it is obvious from the caller standpoint that the call is intended to have side effects. F# type system will not prevent you from such things, so you’ll need a bit of discipline there.

Tests

Writing tests in F# is supposed to be easy. When you write tests, you shouldn’t have to build a big context for each test. If you’ve kept your types and functions simple, your unit tests will not have many dependencies or boilerplate setup. Composition is what functional programming is really about. As soon as your tests feels like wiring things up instead of validating your code behaviour, stand back and try to see if concerns can be separated.

Conventions & whitespaces

I do get that it’s not easy to choose a convention and stay consistent when you’re new to a language, but having a consistent convention regarding spaces makes your code much more pleasant to read (or maybe it’s just me and my OCD). Please do.

Dependencies

Switching to a new language doesn’t mean you should forget everything you’ve learned so far. For instance, the Single responsibility principle is still a good practice! You can think of a function signature as an interface with a single method on it. When you provide a function as a parameter, it’s like injecting the implementation of an interface. Whenever you do it, you should ask yourself whether you really want to inject it. “Do you want to inject a database access function there, or do you want to perform the call somewhere else and just pass in the returned data to the function?”. Every function parameter can be considered a dependency.

Write (or don’t, actually) your own DSLs, Computation expressions, and Type providers

Don’t do that in the first week! I’m totally guilty of using fun and cool features just because I think they’re amazing (and sometimes I want to show off), but try to get the basics right first…

-

DSLs will only prove useful if they’re built on top of well-thought abstractions. Trying to build the DSL first, in order to have a user-friendly readable code, can also lead to overcomplicated implementation underneath.

-

Computation expressions are just syntactic sugar over abstractions. You can probably achieve the same result without them. Try to get your types and concepts right before you find yourself trying to use the “MaintainsVariableSpaceUsingBind” property on a CustomOperationAttribute.

-

Type providers (erased ones, at least) are usually also only syntactic sugar that helps ensure type-safety and convenience. Before writing your own, consider using a simpler approach (but it definitely can make sense to write your own, and if you ever need, you can ping me!)

The advice given here may seem too simplistic, but it can’t hurt, can it?

PS: Now I understand the imposter syndrome

When observing developers in their day-to-day work, it’s quite usual to see them swearing at their programs, because they don’t behave as they should. You often see them asking the program to obey, sometimes cursing, and even praying from time to time. If we take some time to think about it, the main reason why a programmer shouts at a running program is because it doesn’t quite behave as he/she wants it to do. Unfortunately, this is less common in the functional programming community. Having a language that promotes usage of immutability and option types (to name only a few), sometimes deprives you of cursing and praying.

When observing developers in their day-to-day work, it’s quite usual to see them swearing at their programs, because they don’t behave as they should. You often see them asking the program to obey, sometimes cursing, and even praying from time to time. If we take some time to think about it, the main reason why a programmer shouts at a running program is because it doesn’t quite behave as he/she wants it to do. Unfortunately, this is less common in the functional programming community. Having a language that promotes usage of immutability and option types (to name only a few), sometimes deprives you of cursing and praying.

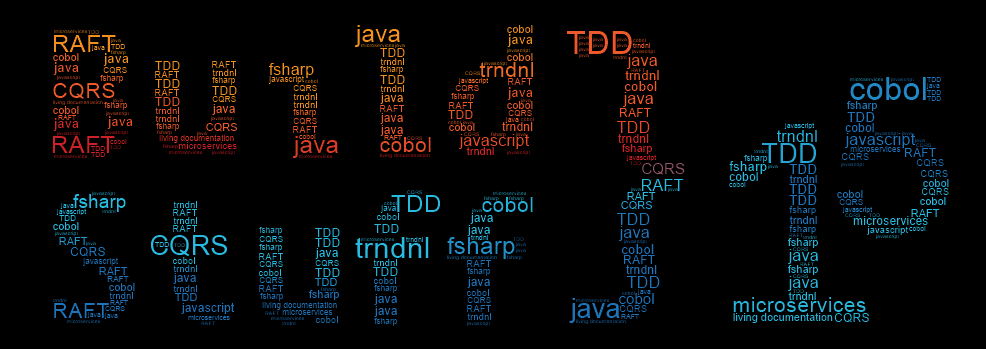

(click on the calendar to view the full size image)

(click on the calendar to view the full size image)